Dropout (Briefly)

One topic that I’ve wanted to briefly cover in a blog post is dropout. When I first encountered dropout some years ago, I found it to be pretty mystical and not particularly intuitive. Dropout is worth knowing as it’s still a key ingredient for regularizing (large) neural networks.

Introduction

Whenever a large neural network is trained there is some risk that it will overfit the training data. Some of the tricks one can employ to combat overfitting are the following:

- Reduce the size of the neural network.

- Increase the training set size.

- Early stopping.

- Traditional L1/L2 weight regularization.

- Ensembling predictions from multiple models.

Dropout (published in 2014) has become another standard trick to help combat overfitting. It is commonly employed when training large langage models like GPT-3 and others.

Mechanics

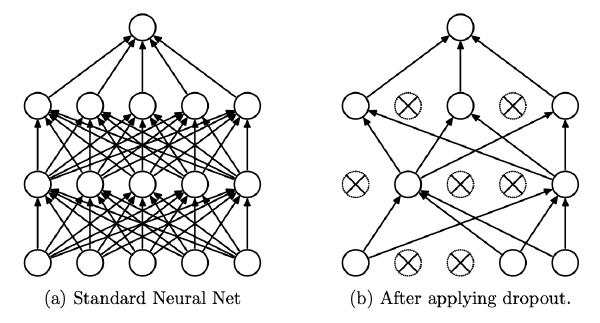

The way dropout works is that during each training step, each neuron has a probability \(p\) of being inactive (dropping out). When a neuron is made inactive (drops out) its output is set to 0. At test time, all neurons will be active.

The figure below illustrates what a neural net may look like at a particular training step when dropout is employed.

Now let’s discuss an important nuance about what happens during training. If we consider some neuron at layer \(L+1\) it will only receive inputs from \(1-p\) of the active neurons from layer \(L\). If we consider \(p=0.5\), then that means on average only half of the neurons (from layer \(L\)) are contributing to the input of this neuron. That means we expect the input to be half as large (on average) as it would be if we had all neurons be active. This ends up being a problem because the inputs the neuron sees at training time will not match what it sees at testing time. To correct for this, we can scale the output of all active neurons in the layer by \(\frac{1}{1-p}\). When \(p=0.5\) that means we would multiply the output of each active neuron in layer \(L\) by 2 which would make the input to the neuron at layer \(L+1\) match what is expected at test time (where no dropout is performed).

Note the method I discussed for scaling at training time is known as (inverted dropout) and differs from the original paper which proposes scaling at test time. Modern libraries like Pytorch implement inverted dropout which has the benefit of not requiring all weights in a network to be scaled at test time.

Intuition For Why it Works

As the original authors state, dropout is a way to combine the predictions of many different neural networks without the computational burden of training many different neural networks and performing inference on all of them.

With dropout we can interpret the network at test time as an ensemble of of many “thinner” (smaller) random networks. This also relates back to the idea that by averaging the predictions of higher variance models we can reduce variance.

Another way to interpret why dropout works is from the lens of preventing too much co-adaptation. An interesting analogy here is that if a basketball team is forced to train with a random half of the players then each player will have to learn to play multiple positions and to play equally well with any of the other players. The team as a whole is more robust.

Conclusion

In this blog post we briefly covered what dropout is and why it works. In practice the dropout rate \(p\) seems to vary quite a bit from model to model (Pytorch defaults to 0.5).

References

All references are linked inline!